Profit №_12_2023, decembrie 2023

№_12_2023, decembrie 2023

Currency convertibility in some transition countries. Early ‘90s issues reviewed in 2018

As strange as it may seem, this article was under preparation for a long, long period of time. It was quite refreshing to discover that many of the early ‘90s issues related to currency convertibility for transition countries are still valid in 2018, almost three decades later. This shows that economic analysis based on facts can easily endure the test of time.

I. Historical context

The problem of currency convertibility for a selected group of countries (Bulgaria, former Czechoslovakia (1), Hungary, Poland, Romania, former Yugoslavia, Republic of Moldova and former Soviet Union) was not a new one. Historically speaking, the measures taken by some countries to introduce currency convertibility were, in fact, a restoration process. However, the domestic and external environment are completely different now in 2018 than almost three decades ago when the transition started. Practice and theory evolved tremendously in a very uncertain economic and political context. Economic performance and social status of these countries have been greatly influenced by the way in which they handled their currencies. And so will continue to be the fate and living standards of hundreds of millions of peoples.

Currency convertibility was a very material topic, especially after 1989 when almost all Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs) chose to make fundamental changes in their political, social and economic systems. The 1991 dramatic changes in the former Soviet Union and its Republics (including Republic of Moldova) again placed this subject in the centre of discussion, but a clear consensus has yet to be reached. Currency convertibility was seen by many economists as a necessary instrument to transform their national economies after so many years of rigid central planning. Of course, currency convertibility was not the only instrument and, more, it should have not been used alone. This instrument was clearly linked with other monetary, fiscal and financial tools.

Some of these countries introduced various forms of currency convertibility, but two key questions arose: should each country achieve it and, more, should it be achieved immediately? The obvious answers were 'yes' and 'sooner is better', respectively, but a hasten decision could have been very risky.

In the post-revolution period, in many CEECs, the concept and the needed measures were widely debated. However, the ways to achieve currency convertibility and sequence of needed measures could not be summarized in a blue print document because the economic and social stages of development of various countries were quite different. Two main theories were advocated at the time by different groups of economists: a 'gradual approach' versus 'shock therapy'. Years after the revolutionary process of transition to a market-oriented econo-my wiped out central planning ideology and practices, many policy-makers realized that 'shock therapy', although desirable, could not have been implemented without considerable risks.

II. (Pre) Conditions and their status of implementation

Being an important subject, everything on currency convertibility was and continues to be debated. Even the terminology was argued. 'Pre-conditions' are of course more than 'Conditions'. The very existence of pre-conditions was some time denied by different groups of economists. Also, economic analysts could not decide if all known pre-conditions or only a part of them would have been necessary before the decision to introduce currency convertibility is taken. Moreover, they were not able to decide of any particular order if the question of prioritization is to be raised. Under such circumstances, the decision-makers acted differently as no other way was possible or recommendable.

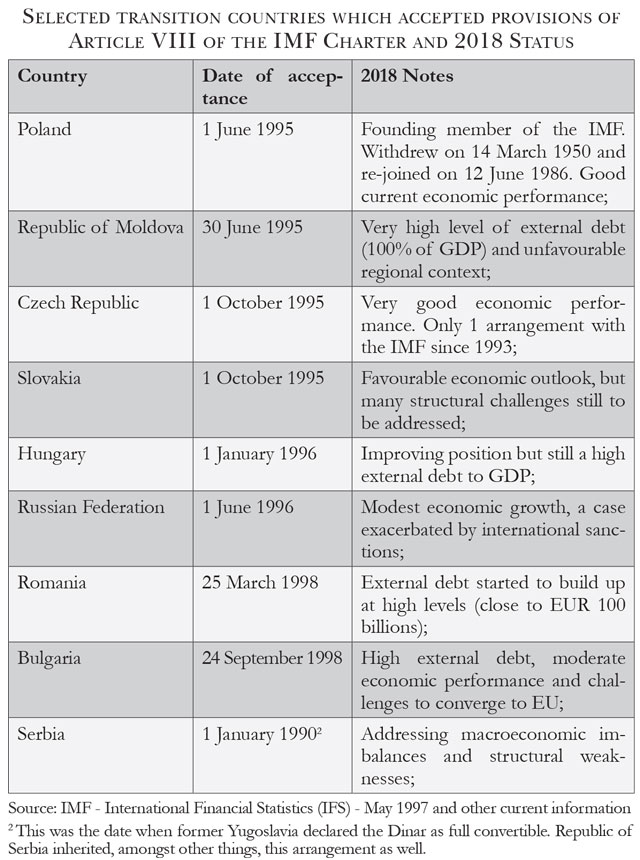

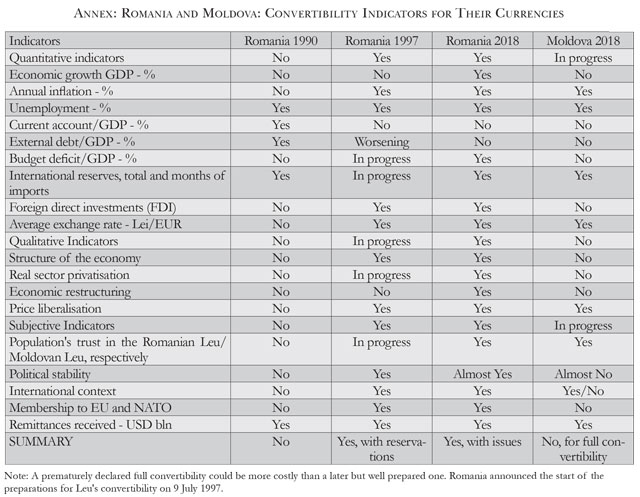

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as of 21 August 2018, a number of 170 countries accepted the obligations of Article VIII of the IMF's Charter, a fact which has been seen as an expression of convertibility. Some 19 countries (out of 189 total IMF members) are in various stages of preparation. Among those still to accept this current account convertibility and eliminate restrictions are also few countries in transition, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and Turkmenistan. A country itself cannot declare its currency convertible without meeting, before or at the same time, some pre-conditions. A closer look at convertibility key pre-conditions is therefore worthwhile. A longer list is presented in Annex for the specific cases of Romania and Moldova, respectively.

Out of the preconditions, the level of international reserves differs largely from country to country, both in absolute terms and as months of imports. For instance, while Poland's total reserve (minus gold) increased up to near USD 4 billion as of end-October 1991, a decreasing trend was registered in those days by Bulgaria, Romania and former Yugoslavia. The former Soviet Union's foreign currency reserves were "close to zero". By the end-July 1991, Hungary and former Czechoslovakia succeeded in keeping the level of total reserves at an almost constant level of USD1.8 billion and USD1.6 billion, respectively. Were these levels adequate in order to achieve or to maintain a full or partial currency convertibility? In some cases yes, but in others no. The answer was not an easy one. Some lessons of modern history were very illustrative: in 1924, the then Soviet Union introduced rouble convertibility and the only result was that it lost 250 tons of gold in three days. Therefore, without enough international reserves, the implementation of currency convertibility could be hazardous.

The equilibrium exchange rate raised first and foremost the question of the appropriate level.

Apparently, an answer to this question was to use the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). But only apparently. In practice, using PPP for CEECs and the former Soviet Union was almost impossible. The simple fact that these countries had distorted domestic prices for decades was the first and most insurmountable obstacle in finding out the right level of the exchange rate. Second, the ex-CMEA countries had also distorted external prices for their intra-trade. In some cases the share of commercial relations developed in transferable roubles was large enough. The World Economic Outlook (October 1991) mentioned that in 1990 between 25 to 40 percent of exports from former Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania and the former Soviet Union went to ex-CMEA trading partners. Needless to mention Bulgaria's case with 70%. The situation is very different nowadays. CMEA was abandoned long time ago and the flows of trade changed significantly. While the theory underlining the PPP was not arguable, its practical implementing methodology is still to be found.

Under those circumstances, many economists and policy-makers soon realized that the right answer on the level of the exchange rate would take some more time. Meanwhile, flexible exchange rate policies were adopted by these countries on a temporary basis, but large fluctuations have occurred. Important misalignments of their exchange rates should have been phased out first. For instance, Poland decided to adopt a gradual devaluation of the zloty, as announced on 15 October 1991. The case of the Soviet rouble was, also, very illustrative from this point of view. The first steps to devaluate the overvalued rouble were taken in early ‘90s. Everybody was shocked in the very beginning when the former Soviet Union accepted that its rouble should be devalued after decades of fixed overvalued exchange rates. The equilibrium exchange rate and its regime have been difficult to be found in those days. By 2018, many issues still remain.

The third pre-condition, price reform or price liberalization was one of the main policy objectives of the reformer Governments in these countries, but from the social point of view, a lot of problems arose. With few exceptions, almost all domestic prices were liberalized with the clear aim to reach parity with the external prices. The price liberalization process was implemented in different ways: some countries went for a sharp decontrol, while others preferred a gradual approach. In all CEECs, hyperinflation was a common word used both by the Governments in power and by the people in the street. The pressure for rapid devaluations of local currencies was evident and a vicious circle of inflation-devaluation-inflation was soon a common reality. Russia's commitment to let the domestic prices free starting January 1992 determined a sharp increase of inflation in a very difficult economic environment characterized, inter alia, by a lot of shortages even for basic goods. And so was the case for the other Republics which follow Russia's example. Therefore, the biggest challenge for all reformers in this group of countries was how to break that vicious circle. This has been an open question since then.

The fourth pre-condition, sound macro-economic policies, was maybe the brightest part of the story, even with a plethora of difficulties. These countries implemented economic programs accepted by international financial organizations like the IMF, IBRD and EBRD. On 5 October 1991, the former Soviet Union signed an agreement with the IMF allowing for an immediate extension of wide-ranging technical assistance. In the very beginning of 1992, the Russian Federation and Azerbaijan Republic have filled applications for membership in the international financial organizations. An immediate membership of the IMF and IBRD was advocated then by different economists for all former Republics. Moldova became a full member of both the IMF and World Bank Group on 12 August 1992. Others also applied soon. Thus, these countries had a chance to promote sound macro-economic policies in their own interest.

Finally, the problem of external viability for CEECs and for the CIS could be labelled as uncertain, at best. Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria and former Yugoslavia (inherited by Serbia and other Western Balkan countries) had large external debts. Nowadays, some of them are still heavily in debt. In 1991, debt service payments for the whole group reached 19% of their exports of goods and services as compared to 14% in 1990. The projections for 1992 were even higher, at 21%. Their access to the international capital markets was not uniform. Moreover, in 1991, many of these countries faced large external financing gaps and the estimations for future were not very optimistic. The leading industrial countries discussed about some 'debt alleviation' and/or better market access. Improvement of terms of trade was also required. Concessional financial flows and higher investments in this area had also a good impact. Without a viable external equilibrium, the efforts undertaken by these countries to maintain or to introduce convertibility of their currencies would have been seriously damaged.

Evidently, there was no unique prescription on how these countries should have handled their currency convertibility or on how to achieve it. A case-by-case approach was a valid approach. However, any individual decision taken by any country should have been based on strong economic, financial and monetary criteria to avoid high risks, which was not always the case.

III. Romania and Moldova's cases: past and recent experience

As mentioned, historically speaking, some transition countries were in a restoration process. Romania was an interesting case, but Moldova has a very different story all together.

The first Romanian currency put into circulation in 1867 was freely convertible. In fact, three coins of 20, 10 and 5 lei were made from gold and others from silver (see the law published in 'Monitorul' no. 89 dated 22 April/4 May 1867). The national currency, the Romanian leu, was freely convertible up to 1914 when the World War I started. The second period in the leu relatively short history which is worthwhile to be mentioned was between 1929-1933. According to the Law on stabilization, in 1929 the banknotes issued by the National Bank of Romania (NBR) were declared free convertible in gold or foreign exchanges. However, because Romania's foreign exchange reserves declined sharply from 3.6 billion of lei on 9 March 1929 to 80 million of lei in February 1932, the leu's status as a free convertible currency was suspended.

The whole period of the following years up to 1989 had not too much to be noted in this field, except, maybe, three different facts: a) all these years the leu exchange rates (commercial, non-commercial and or especially the official one) were usually overvalued; b) there was a 1974 public declared goal of convertibility for the Romanian leu which never was reached; and c) during this period, Romania became a full member of the IMF and the World Bank Group in December 1972 (see left picture above).

Immediately after the December 1989 Revolution, the new Romanian authorities introduced bold measures in this field. First, even in the very latest days of December 1989, the foreign exchange regime was relaxed. Second, on 1 February 1990, the commercial and non-commercial exchange rates of the leu were unified at 21.00 lei/Dollar (from 8.74 lei/Dollar and 14.23 lei/Dollar, respectively, as of end-January 1990). But this was not yet the equilibrium exchange rate. It was just a step. On 1 November 1990 a new depreciation of the leu took place. The new rate was fixed at 35 lei/Dollar. At the same time, the first phase of a bold reform of domestic prices was started. On 1 April 1991 a next step was implemented with 60 lei/Dollar and with the second phase of price liberalization. Other structural measures like land reform and privatization of some state-owned enterprises started in 1991 (see Annex). Also, in August 1991, the first inter-banks market was organized in Bucharest after more than four decades of central planning economy. A new exchange rate for leu started to be quoted daily. Its level was almost all the time over 200 lei/Dollar. A dual exchange rate of leu was in place until 11 November 1991 when the exchange rate of leu was unified once again at 180 lei/Dollar. An 'internal convertibility' or more precisely a 'current account convertibility' was introduced. Meanwhile, the leu went through a new denomination in which 10,000 old lei (ROL) were exchanged for one new leu (RON) on 1 July 1995. The leu's future could, however, be considered as opened too. Future structural reforms and tight fiscal and monetary policies will be further needed. A favourable external environment is crucial. An adequate and responsible management of the external debt (which is rapidly approaching EUR 100 billions) is highly required.

In parallel, on 29 November 2018, Moldova will celebrate the 25-th anniversary of the birth of its “young” currency. This was done with the full support of the IMF as Moldova became a full member on 12 August 1992 (see right picture above). After five years of stable evolution, the Moldovan leu suffered the first serious shock in the aftermath of the 1998 crisis. A second material depreciation followed the 2014 banking fraud of USD 1 billion, of which today not very much was recovered despite international assistance in this respect. Since March 2016 a new Governor and a new management team were appointed at the National Bank of Moldova (NBM). There are high expectations that the Moldovan banking sector will be cleaned up and that the current account convertibility introduced by Moldova on 30 June 1995 will be consolidated. However, the country does not appear to be ready at this stage for full convertibility of the Moldovan leu, as presented in Annex.

Both cases of the Romanian leu and Moldovan leu, respectively, have lessons to be learned from the accumulated (longer/shorter) experience. A convertibility status (partial or full) is not necessarily declared by administrative means/acts. It should be prepared and gained first. Understanding this basic requirement (which was not always the case) by authorities and monetary decision makers is imperiously needed.■

______________________________________________________________________________________

(1) Historical changes happened during the last three decades. At least three states from the selected group disappeared since 1991. Czechoslovakia was a Central European state (from October 1918 up to its dissolution on 1 January 1993). Czech Republic and Slovakia are the legal successors. Yugoslavia had a violent dissolutions, a process which is not yet entirely settled and the Soviet Union was split in the 15 states, of which the key successor was the Russian Federation.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Alex M. Tanase is an Independent Consultant and Former Associate Director, Senior Banker at EBRD and former IMF Advisor. These represent the author's personal views. The assessments and views expressed are not those of the EBRD and/or IMF and/or the World Bank and/or NBR and/or NBM and/or indeed of any other institution quoted. The assessment and data are based on information as of end-August 2018.

Adauga-ţi comentariu