Profit №_12_2023, decembrie 2023

№_12_2023, decembrie 2023

Republic of Moldova - the birth of the banking sector. The first decade

This year, on 8 May, the largest commercial bank of the Republic of Moldova (Moldova in this article) marked the 30th anniversary of its establishment. The legal act which provided for the establishment of this bank was a Government of Moldova’s Decision dated 8 May 1991 through which the activities of former Soviet Union’s bank branches/divisions were transferred to a newly established Moldovan bank. The year 1991 could be considered the year in which the Moldovan banking sector was born taking into account that on 4 June 1991 the National Bank of Moldova (NBM) was also founded. The complex evolutions which followed in the first decade (1991 -2001) were to predict major changes, some of which were dramatic.

(This article was taken from the Magazin Istoric*)

This is how was established the Commercial Bank Moldova Agroindbank (MAIB), which inherited the branches/divisions of one former Soviet bank specialised for transactions in the agro-industrial field and cooperative trade. Shortly thereafter the Commercial Bank Moldindconbank (MICB) followed and it took over the financing activities of industry and capital constructions. MICB was established on 25 October 1991 through the reorganisation of the State Bank for Industry and Constructions of the former USSR. This had a tumultuous evolution, intertwined at certain stages in time with Investprivatbank, a bank that is currently under liquidation. Banca Sociala (BS), currently in liquidation since 2016 in the aftermath of a resounding fraud, unique in the history of the transition period (estimated at $1 billion and still to be clarified), took over the banking activities for municipalities, state-owned trade and catering for individuals. A very special case was that of Banca de Economii (BEM)/Savings Bank, also in liquidation since 2016, together with Banca Sociala and Unibank, which took over the activity of the former Saving House. It was subsequently transformed into a bank designed to additionally serve private mortgage lending. One other bank, Eximbank, was established a little bit later on 29 April 1994 through a reorganisation process as well.

The commercial banks mentioned above, which took over the activities of the territorial divisions of the Soviet banks, had implicitly assumed (apart from the pure commercial activities) the burden of the expenses related to free of charge services granted (up to 1998) for public finance accounts and to a large number of budgetary institutions. All these new banks were established as closed joint-stock companies, in accordance with the Government Decision already mentioned, but in 1997 legislative changes were introduced, under which these were transformed into open joint-stock companies. At the same time, within a few years after 1991, the shares owned by the state were bought by the respective banks. The shareholding of commercial banks during the first decade of transition was extremely diversified, including companies and individuals. There many cases in which the number of shareholders was in their thousands, of which some of the shareholders had, in reality, one or just a few shares. In practice, this led to a strange situation in which the major decisions of corporate governance were taken by shareholders with a small number of shares and which started to form various groups of interest. Some of these groups in evolved forms to a certain extent, of course, are still in existence today. However, there were cases in which some shareholders did not show the required transparency in accordance with the international standards.

All these new banks were established as closed joint-stock companies, in accordance with the Government Decision already mentioned, but in 1997 legislative changes were introduced, under which these were transformed into open joint-stock companies. At the same time, within a few years after 1991, the shares owned by the state were bought by the respective banks. The shareholding of commercial banks during the first decade of transition was extremely diversified, including companies and individuals. There many cases in which the number of shareholders was in their thousands, of which some of the shareholders had, in reality, one or just a few shares. In practice, this led to a strange situation in which the major decisions of corporate governance were taken by shareholders with a small number of shares and which started to form various groups of interest. Some of these groups in evolved forms to a certain extent, of course, are still in existence today. However, there were cases in which some shareholders did not show the required transparency in accordance with the international standards.

The accounting standards started to be adjusted to the practice existent in the developed countries and the first international audits were prepared based on the 1993 accounts by the international auditing company KPMG. At the same time, during the first part of the first decade of transition, the new banks had transformed themselves into universal banks and in time some of them were listed at the Moldovan Stock Exchange, although the stock exchange’s liquidity was very low in those days.

From the very beginning, the largest commercial bank in Moldova was MAIB. As of end-1991, this bank has entered the transition period with a balance sheet of 28.9 billion Soviet rubles and managed through adequate managerial policies to grow its assets, total equity, the total number of clients, lending portfolio and attracted deposits (currently, MAIB’s total assets reached 30,996 mln Lei (€1,452.3 mln).

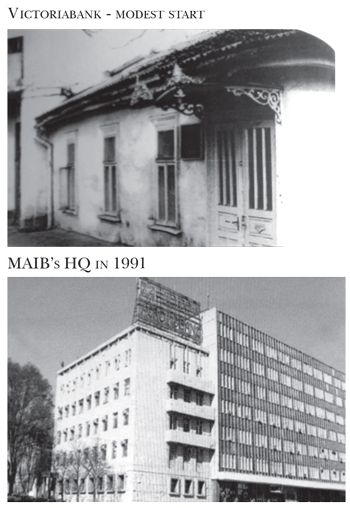

In the historical context which prevailed in those years, Moldova had surprisingly offered a favourable environment for the development of private banks, even before the dissolution of the former Soviet Union. The case of Commercial Bank Victoriabank (VB) is very illustrative. This was established on 22 December 1989 through a collection of money from population and companies or through by taking over of some of the clients from other commercial banks. In a very convoluted period of time in which the Soviet Union had disintegrated, on 22 February 1990 the founder and the main shareholder of VB did manage to register the new bank with the former State Bank of the USSR (licence no. 246). A little bit later, the first transaction was booked on 12 April 1990 and, on 1 September 1991, VB was reorganised as a joint-stock company and reregistered with the NBM. After many institutional difficulties, this bank managed to remain operational with the support of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), which provided credit lines and participated in the capital of the bank as well as other international financial institutions. This bank was the first and the most illustrative example of the enormous difficulties the commercial banks had to deal with during the first decade of transition. Currently, Victoriabank is ranked as the third bank of Moldova, with total assets of 15,787 mln Lei (€740 mln as of end-February 2021). Starting with 2018, VB is part of Banca Transilvania Group, Romania. EBRD is still an indirect shareholder through an investment vehicle registered in the Netherlands.

In the historical context which prevailed in those years, Moldova had surprisingly offered a favourable environment for the development of private banks, even before the dissolution of the former Soviet Union. The case of Commercial Bank Victoriabank (VB) is very illustrative. This was established on 22 December 1989 through a collection of money from population and companies or through by taking over of some of the clients from other commercial banks. In a very convoluted period of time in which the Soviet Union had disintegrated, on 22 February 1990 the founder and the main shareholder of VB did manage to register the new bank with the former State Bank of the USSR (licence no. 246). A little bit later, the first transaction was booked on 12 April 1990 and, on 1 September 1991, VB was reorganised as a joint-stock company and reregistered with the NBM. After many institutional difficulties, this bank managed to remain operational with the support of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), which provided credit lines and participated in the capital of the bank as well as other international financial institutions. This bank was the first and the most illustrative example of the enormous difficulties the commercial banks had to deal with during the first decade of transition. Currently, Victoriabank is ranked as the third bank of Moldova, with total assets of 15,787 mln Lei (€740 mln as of end-February 2021). Starting with 2018, VB is part of Banca Transilvania Group, Romania. EBRD is still an indirect shareholder through an investment vehicle registered in the Netherlands.

After VB, the formation of new private commercial banks had continued, so by the end of 1995, the Moldovan banking system was formed of 27 commercial banks and three branches of foreign banks from Romania and Transnistria. Out of the 27 commercial banks, 17 had licences for all domestic and international activities. The analysts of the Moldovan banking sector of those years had repeatedly commented that Moldova was in fact "over-banked". Currently, only 11 commercial banks have valid operational licences in Moldova, out of which most of them are owned by well-known foreign shareholders.

All these banking evolutions were possible in the historical context of those years from the start of the transition. On 27 August 1991, Moldova declared its independence, but the NBM was already established on 4 June 1991, with the specific attributions of a central bank. In June 2021, NBM marked its 30th anniversary, a fact which was underlined during the virtual seminar organized by the NBM on 7 April 2021. The seminar has benefited from the participation of the Governor of the National Bank of Romania, the academician Mugur Isarescu, which underlined that the independence of the central bank was "essential".

Back to the historic context, it is worth noted that Moldova started its preparations to become a member of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and of the World Bank Group in 1991, immediately after the independence declaration. This process, in which I have participated, was a very difficult one. All macroeconomic indicators of the newly established state were in accordance with the old methodology and socialist practice, in which the former USSR played a major role. The introduction of the banking terms expressed in the Romanian language (which in itself struggled to get through in a society which for five decades up to 1991 was educated in the Russian language) was a difficult and long process in which the international financial institutions (IMF and others) had played a key role. The transition from the macro-economic socialist indicators to those specific to market economies was a real qualitative jump. Finally, Moldova’s membership to the IMF, in which I have directly participated from the IMF’s side, was signed by the then Prime Minister, Mr. Andrei Sangheli, on 12 August 1992. At the same time, Moldova became a member of the World Bank Group.

At the beginning of its activities, the NBM had a very restrictive monetary policy. The IMF’s recommendations were strictly implemented, which contributed to a greater extent to control some turbulent economic developments which today could be easily labelled as economic derailments. Despite all of these, the refinancing rate for commercial banks reached 377% by March 1994, a very unusual level on the domestic lending markets. Also, the minimum reserves requirements for commercial banks were very high (in 1994 - some 28%). A step by step relaxation process of these though economic policies had followed. For instance, the refinancing rate was gradually reduced up to 19% in April 1996. Minimum reserves requirements were also reduced to 8% by the end-1996.

All these efforts made by Moldova during the difficult transition process to a market economy were recognised by the international community. Moldova succeeded to obtain good ratings from the main international rating agencies in the ’90s. This advantage was lost because of the serious negative political, financial and banking evolutions, especially during 2012 - 2015. Concerning the national currency, Moldova is a special case. After its independence, this country continued to use the Soviet ruble, then the Russian ruble and its coupons up to 29 November 1993, when, with the help of the IMF, it decided to introduce its own national currency (the Moldovan leu). The first Moldovan leu was signed by the first Governor of the NBM, Mr. Leonid Talmaci, who held this office for the longest period of time.

Concerning the national currency, Moldova is a special case. After its independence, this country continued to use the Soviet ruble, then the Russian ruble and its coupons up to 29 November 1993, when, with the help of the IMF, it decided to introduce its own national currency (the Moldovan leu). The first Moldovan leu was signed by the first Governor of the NBM, Mr. Leonid Talmaci, who held this office for the longest period of time.

During the first years of its existence, the Moldovan leu managed to remain stable against the reference currency in Moldova in those years, namely the USA dollar, around its initial introductory exchange rate of 3.85 lei/USD. This had a positive impact on the commercial banks, but the great financial crisis on the international capital markets from August 1998 gave a hard hit to the banking stability in Moldova and the Moldovan leu started a very steady process of depreciation (18.01 lei/USD in April 2021). This depreciation was also heavily impacted by the accumulation, during the first decade of transition after independence, of a certain external debt.

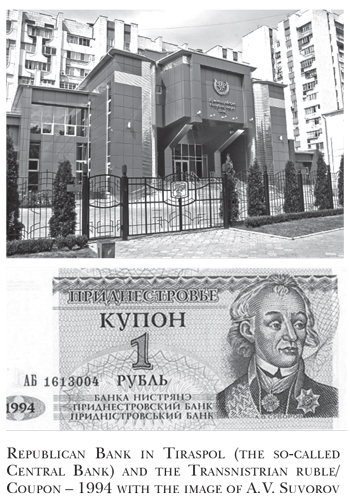

One characteristic feature of the Moldovan banking system is the presence of the second central bank in the so-called Transnistrian Moldovan Republic. Transnistria, which had a population of around 469,000 persons in 2018, was never recognized by the international community, except by the Russian Federation, as a distinct state. Between Moldova as such and Transnistria did exist and they still have a border, although they are part of the same internationally recognised state. During the ’90s years of the last century, crossing from Moldova to Transnistria was possible only after custom formalities which tended to be very detailed, especially when in the delegations in which I was part of there were foreign citizens from the developed countries. The controlling border force on the Transnistrian side was very suspicious and the required waiting time was usually very long, based on reasons which in Europe were labelled as hilarious. In many cases, the support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from Chisinau was needed before the delegations were allowed to cross the border to fulfil their jobs.

During the first decade, some Moldovan banks (such as Victoriabank and MICB) used to have branches on the left bank of Dniester River at Tiraspol or Slobozia, one aspect which involved substantial banking risks. The control of the activities developed by these branches was very difficult to be undertaken in real life. The dialogue with the so-called central bank (Transnistrian Republican Bank), which had issued the Transnistrian rouble, was very difficult, as many companies acting in this region used to have non-transparent activities and therefore there was no interest for dialogue or cooperation.

Currently, the Moldovan banking system does not include banking institutions in the territory on the left bank of Dniester River, as all the branches in this region were closed upon the recommendation of Moldova’s foreign partners. Despite all advantages gained at their establishment (through the reorganisation of the regional Soviet branches), all Moldovan commercial banks were rather small as compared to the banks in other transition countries. Banca Sociala and BEM had disastrous endings after many years of bad management, especially during the last decade. BEM had navigated through a continuous process of contradictory changes regarding its shareholding. Finally, the state lost its control of the share capital of the bank and became a minority shareholder. Since 2016, the bank has been in liquidation. Apart from the three banks involved in the fraud of the century (Banca de Economii, Banca Sociala and Unibank), many other banks (11) became bankrupt during the last three decades or are under liquidation. Some of them had various destinies, but in essence, they did not observe the basic norms of banking regulations. With some of these banks, I worked effectively until the shareholders started to adopt measures that were not according to sound banking principles and with the requirements of transparency.

Despite all advantages gained at their establishment (through the reorganisation of the regional Soviet branches), all Moldovan commercial banks were rather small as compared to the banks in other transition countries. Banca Sociala and BEM had disastrous endings after many years of bad management, especially during the last decade. BEM had navigated through a continuous process of contradictory changes regarding its shareholding. Finally, the state lost its control of the share capital of the bank and became a minority shareholder. Since 2016, the bank has been in liquidation. Apart from the three banks involved in the fraud of the century (Banca de Economii, Banca Sociala and Unibank), many other banks (11) became bankrupt during the last three decades or are under liquidation. Some of them had various destinies, but in essence, they did not observe the basic norms of banking regulations. With some of these banks, I worked effectively until the shareholders started to adopt measures that were not according to sound banking principles and with the requirements of transparency.

A special note is worthwhile to be made for the commercial banks which were subsidiaries of some banks from Romania, as was the case of Banca Turco-Româna (Turkish-Romanian Bank) and Bankcoop. The fate of these banks in Romania is well-known, but their images in Moldova had suffered heavy blows once the main banks had entered into the bankruptcy procedures at home. At the same time, one other thing which should be noted was related to the fact that the NBM had not been up to the statutory and/or international standards regarding the supervisory role-specific to a central bank if we refer to the banking fraud, the Russian Laundromat or the bankruptcy of some commercial banks.

Finally, we just express our hope that this modest endeavour will serve as a departing point for an encyclopaedia for the next generations with all major historical events from the Moldovan banking sector, especially more so that the first two largest commercial banks and NBM celebrate this year three decades from their establishment. The lessons learned from this short presentation of the birth and consolidation of the Moldovan banking sector are multiple, starting with the need for constant and high-quality banking supervision. Even more, the way the commercial banks evolved at the start of the transition is a confirmation that banking transparency is a fundamental condition for a healthy banking system, a field in which trust is the most precious asset. Without the implementation of verified banking principles as applied in developed countries, the corporate governance of the commercial banks is indeed liable to damages and the end (the bankruptcy) is of course undeniable sooner or later. The cooperation with the international financial institutions has also proven many times as beneficial for Moldova and its banking system. Like for all other countries in transition, as a matter of fact.■

These are the author’s personal views. The analysis and expressed opinions are not those of the NBM and/or of any commercial bank and/or and any other quoted institutions. The analysis and the data are based on information available by mid-April 2021.

* This article was published in the Romanian language only for the first time by the Magazin Istoric Revue, Romania no. 6/June 2021 signed by the same author.

Adauga-ţi comentariu