Profit №_12_2023, decembrie 2023

№_12_2023, decembrie 2023

Some key macro-economic correlations: Why are not they working for Moldova yet?

For any healthy economy, the national currency represents an indicator of extreme importance which ensures the normal functioning of the whole economic system. You will find out in the paper below how the things evolved in the Republic of Moldova since the introduction of its national currency and why some key macro-economic correlations are not working for Republic of Moldova yet.

For any healthy economy, the national currency represents an indicator of extreme importance which ensures the normal functioning of the whole economic system. You will find out in the paper below how the things evolved in the Republic of Moldova since the introduction of its national currency and why some key macro-economic correlations are not working for Republic of Moldova yet.

Historical, regional and monetary context

Moldova became an independent state on 27 August 1991, in the aftermath of the Soviet Union's dissolution. One year later, in August 1992, Moldova became a full member of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank Group. The memberships in these both financial organisations represented an important achievement for the new Moldovan authorities. As originally hoped, by achieving membership in both international institutions, Moldova benefited, first and foremost, of the financial support for its reforms to a market economy. Also, Moldova received technical assistance, including training for key Moldovan staff from the banking and public financial sector. The most recent facilities were (EFF and ECF) for a total amount of SDR 129.4 million (USD 178.7 million) were signed with IMF on 7 November 2016 and is disbursing. The conditionality of this last program is rich, especially on the banking sector supervision and restructuring of this key sector. However, more importantly, Moldova's cooperation with both the IMF and the World Bank Group (including the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA)) helped it to have access to international capital markets, to obtain good international ratings and finally to negotiate and sign, on 27 June 2014, a Deep Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA or Association Agreement) with the European Union (EU).

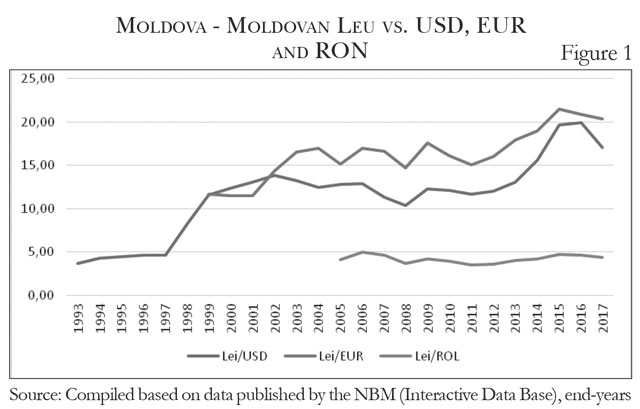

A bold decision to introduce its own currency was taken and that happened on 29 November 1993, when, with the support of the IMF, Moldova put in circulation its own Moldovan Leu (the Leu). From an economic point of view, some conditions for a stable currency had been met in those days, such as the lack of any foreign debt and the economic potential of the agri-business sector. These premises were of major importance, but it should be noted that Moldova barely had any foreign currency reserves and had no gold holdings whatsoever at the time when this new currency was ″born″. In the dissolution process of the former Soviet Union, Moldova opted for ″no share of the foreign debt, no share of the international assets″. However, the lack of any gold holdings has haunted the currency up to nowadays.

The economic potential of this country was quite good if compared to its geographic and human dimensions, but it was not used to the highest level. By the time of the introduction of its currency, Moldova had registered a sharp economic decline. Inflation and state budget deficits was extremely high. Hence, the evolution of this new currency was to follow more dramatic developments in the following years, as presented below.

Under such circumstances, corroborated with the second large scandal in the banking sector in 2015, the currency depreciated to 20.41 lei/EUR and to 17.10 lei/USD, respectively, as of end-2017. It is true that a modest appreciation was registered (mainly vs. USD) by the end of the last year and the first part of 2018, but during 2015-2016, the level of 22.00 lei/EUR was exceeded repeatedly which shows the weakness and the fragility of this young currency.

A decade of chronic deficits and debts

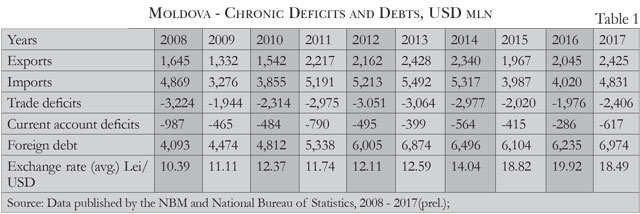

Over the last decade, Moldova registered significant twin trade and current account deficits as presented below:

In the winter of 1996, Moldova was forced to introduce the ″state of emergency″ as the Russian Federation reduced its exports of oil, natural gas and energy and asked for the upfront payment of the accumulated debt. In more recent years, Moldova had another type of difficulties generated by restrictions and/or by the total prohibition of exports of some traditional products to the Russian markets. This was supposedly done for phytosanitary reasons, but all external analysts of the Moldovan developments agree that the restrictions were mainly geo-politically motivated. Also, the Russian authorities threatened many times that all work permits of the Moldovans working in Russia (around 400,000 according to some estimations) will be withdrawn. This is a major risk for the Moldovan currency as a large part of remittances comes from Russia, for the two trade and current account deficits and for the level of foreign debt itself.

Despite the so called zero option (no foreign debt, no external assets), Moldova's foreign debt started to accumulate at a rapid pace. By end-2017, it built up to a staggering level of USD 6.97 billion. This was already equal to approximately 100% of GDP. The Moldovan foreign debt has had and will continue to have a material impact on the fate of the Moldovan Leu and on other key macro-economic correlations. In addition, the debt accumulated by the companies established in Transnistria has been and will continue to be a topic of heated discussions in the Moldovan society, as the break-away unrecognized Republic of Transnistria has been supported by the Russian Federation ever since Moldova's independence in August 1991. Moldova has been and will continue to be externally vulnerable because of its almost total dependence on energy imports from the Russian Federation and other CIS countries.

Lack of responsiveness to leu's exchange rate changes

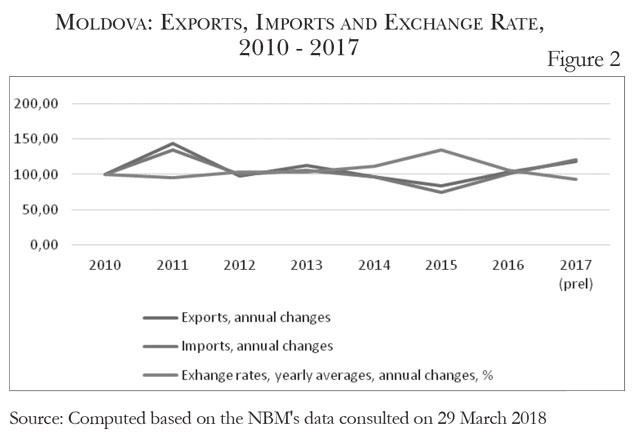

There is almost a general agreement in the economic theory that a depreciation of a currency of a certain country will lead to increase of its exports and to a reductions of its imports. According to the classical economic gospel (see D. Ricardo, C. Kiritescu, J. Stiglitz and many others), the exporters will benefit from a devalued currency as they will cash more in their local currency, while importers will have to pay more in local currency for their imported goods. In turn, the importers will have to increase their wholesale prices and finally the retail ones. This will reduce the demand for imported goods, but inflation will start to nudge up and further depreciations of the currency will be the natural result. The spiral of ″depreciation-inflation-depreciation″ will soon be a common reality. All seems to be correct from a theoretical point of view and there are cases when the correlations between exports, imports and exchange rate changes worked (see the cases of Russia's imports and rouble changes between 1990 - 1995 and that of the Czech Republic's exports and change of its currency during the same period). All good, except that, in some cases, this theory does not work in real life for very different reasons. Moldova is an illustrative case in this latter respect.

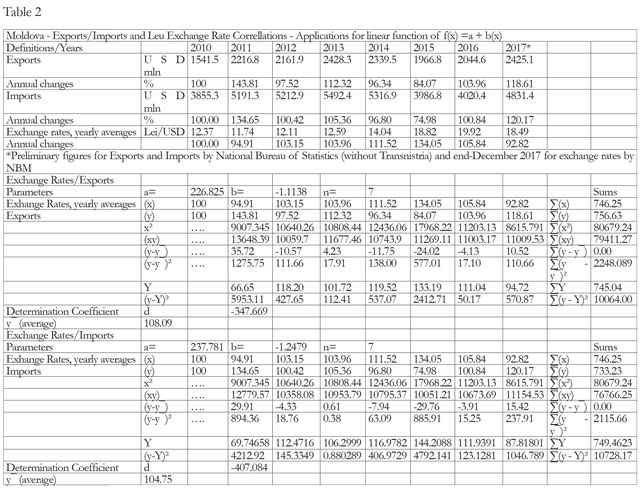

A mathematical analysis of Moldova's exports and imports changes, respectively, (defined as two axes of y), equivalent in USD for the last 7 years, in correlation with the annual changes (axe x) of the Moldovan Leu' exchange rate against USD could be done using a simple linear regression function such as, for example, f(x) = a + bx. This could be used to test the strength of correlation (or lack of it). A system of double equations needs to be resolved, namely:

n a + b ∑x = ∑y (1)

a ∑x + b ∑x2 = ∑xy (2)

where:

n = number of the years in the selected period;

a and b = parameters of the selected regression function.

Based on data above, the resulting parameters (a and b) showed no correlation during the last 7 years searched for this paper in Moldova's case (see primary data in Table 1). In order to find out the “determination coefficient” (d) of this linear regression function, the following formulae could be used:

where: Y = theoretical function of the searched series.

In other words, MD Leu's exchange rate changes (depreciations/appreciations) did not have any major impact on the exports' value changes, due to the reasons presented below. Same was true for imports. The results for (d) show clearly no correlations between the two pair of series. A way to verify the correlation is offered to practitioners by Microsoft/Excel, where the following mathematical formula is offered for CORREL function:

where: ¯x and y¯ are average of the first and second series, respectively.

If this latter formulae is applied on the series of changes resulting from the original figures presented in Table 1, the direct positive correlation showed is inexistent for Exchange rate changes and Exports changes (+0.0334). A negative correlation (as is supposed to be) is also very weak for the case of Exchange rate changes and Imports changes (-0.5486). In fact, this resulting level is treated in practice as no correlation. These results are clearly illustrated by the trends in the figure 2.

Some explanations - disturbing factors

Basically, both the correlations and the graph show that during this period of 7 years, the evolution of the Moldovan exports and imports did not follow the script. Some of the possible reasons why it happened so are explained, in summary, below:

• First and foremost, the Moldovan economy inherited from the former Soviet Union was structured and focussed on the markets of the former Soviet Union and the former socialist countries, members of the former Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon, in existance between 1949 and 1991, that comprised many countries, such as the former Soviet Union and the former Eastern Bloc). After its independence, Moldova needed years to restructure its economy and the restructuring process was slow due to, inter alia, the fact that the majority of its industrial assets were located in Transnistria, a break-away republic unrecognized by the international community. This was a stumbling block for the Moldovan authorities for decades up to nowadays;

• Second, Moldova was and still is a majority agri-business economy, with key industries such as canning of fruits and vegetables, wine industry and other processing branches closely related to the erratic agricultural crops. In many years, Moldova's productions of fruits and vegetables were (partially or even totally in some years) destroyed by late spring colds, freezing or even snows after the agricultural season already started. In turn, this has heavily impacted on the export potential of the country which made the right theoretical correlations mentioned above almost useless;

• Third, for many years after its independence, Moldova was at the mercy of a capricious geo-political environment, caused by the great powers in the region. As mentioned, in March 2016, the Russian Federation introduced restrictions on the exports of some traditional Moldovan products. The country has had its exports of traditional fruits, vegetables, wine, cognac, meat, etc. blocked on the Russian markets for many years since then. Also since then a continuous game was played by the Russian authorities (mainly Rosselhoznadzor and the Federal Service for Monitoring Consumer Protection and Human Welfare - Rospotrebnadzor,) to allow or to prohibit large consignments of Moldovan products. In many cases, many perishable goods were returned from wholesale stores in Russia with all the damages (perishable goods deteriorated) and costs being covered finally by the Moldovan exporters (who barely can afford it). Other restrictions were introduced before the signing in 2014 by Moldova of the DCFTA with the EU and again in February 2017. The results of such prohibitions were very harsh for the Moldovan exporters of wines and other related products. For instance, exports of this group of products declined from USD 235 mln in 2005 to USD 61 mln in 2012, to give just an example. This was done apparently for phyto-sanitary reasons, but all the analysts following the Moldovan developments agree that the actual reason was the geo-political game played in the region by the great superpowers. Of course, Moldova made every efforts to re-direct its traditional exports to other markets such as the EU and China, but this has been a very long process which requires time and moreover which implies a lot of additional costs;

• Fourth, on the imports side, Moldova is again in a special precarious situation as it has been and continue to be totally dependent of the imports of energy (oil, natural gas, electricity and the likes) from the Russian Federation and other CIS countries. This again made the theoretical correlations redundant. Moldova tries to import more energy products from Romania, but Romania itself is not self-sufficient from this point of view. Same for Ukraine. Moreover, pipelines were needed to technically connect Chisinau and other parts of the country with Romania. Construction started, but there are connection problems yet;

• Fifth, although not exactly the same as exports, services' trends did not observes the right correlation either. Despite the depreciation of the Moldovan Leu (especially after 2014), the level of remittances (transfers of some one million of Moldovans working abroad) did not increase accordingly, as it theoretically should. In fact, the reverse is true, with the last years on records registering a visible downward trend. Many countries in which the approximatively one million of Moldovans are living and working introduced a lot of restrictions, the most of which being introduced by the Russian Federation. Obviously, no correlation was observed, as the restrictions in transferring money to Moldova were mainly of political nature. Despite all these problems, Moldova received during the last 10 years, on annual basis, an average USD 1.3-1.4 billion from its citizens currently living and working in the Russian Federation, the European Union, USA, United Kingdom, Israel and many other countries. An amount of USD 1.2 billion was registered in 2017. In some years, this represented up to 20% of the Moldovan GDP, but the large majority of this money is going for consumption/subsistence. As such, the Leu's exchange rate and Moldova's current account status have been clearly related to the volume of remittances. The large transfers helped considerably the financing of the trade deficits and the Moldovan Leu to stay afloat, but if the total level of remittances will decline (as seem to be the tendency of the last years), the exchange rate of the Leu will clearly be negatively impacted. No doubts that pressure on the currency and finally on exports/imports will continue without a solid stream of remittances. The ratio of consumption/investments will be also influential and the increase of the investment share will help supporting the Leu and reduce the deficits;

• Last but not least, the Moldovan exports and imports (like in the case of many other countries) are implemented in many currencies. The figures presented in Table 1 are simple transformations of various transactions denominated in many currencies into USD. As such, the Leu's exchange rates (which are not entirely dependent of Moldovan developments only) will impact on the correlations in various directions. The result is that the ″determination coefficients″ of the chosen regression function are very weak or even negative as presented above.

Many other reasons could be added to this very short list of ″disturbant″ factors which explains why a very good theoretical approach is not working in Moldova's case. The situation of this landlocked country may not be unique, in fact. Countries which base their economies on one key commodity (such as crude oil exporting ones) may encounter similar mishaps when coming to fundamental economic correlations. Also, countries which are caught in the middle of geo-political games or even military interests or war zones may well suffer from the same issues as Moldova does. Unfortunately, no easy solutions are immediately available to resolve this economic anomaly despite all good efforts of the international community, international financial organizations and/or of the respective countries themselves.

External imbalances - do they matter?

Of course, they do. It is quite clear that countries with large external imbalances (such as the USA, United Kingdom, Greece, Romania, Serbia, Macedonia (FYROM) and many others) should be concerned. Basically, these are at the mercy of ″the kindness of strangers″, as Tennessee Williams put it in its famous play ″A Streetcar Named Desire″ (played also in some Eastern European countries even under the communist times). Rebalancing the books (external accounts in this case) will mainly depend on the willingness of other commercial partners to take the goods offered by the debtor countries. Even more, of crucial importance will be the ways of financing of deficits (increase of the capital account surpluses, borrowing on international markets, attract more foreign direct investments, including through more privatisations, internal financial and budgetary discipline, eradicate corruption, etc.). Mutatis mutandis, Moldova is in the same ″club″. All above options could be used, but as the country has already experienced, during its 27 years of transitions to a market economy since its independence in 1991, some of its key commercial partners, especially those with a geo-political influence in the region, does not seem very prepared to buy the Moldovan goods/services without political interference.

The present political situation in the region is very sensitive/complex. The fact that the Moldovan macro-economic developments did not show the right correlations (exchange rate changes, exports and imports test is just one example) does not mean that they will never function. In a right political and economic environment, these fundamental correlations will work and the Leu's evolution and its impact on exports and imports will be more predictable. Not for the time being though. The Moldovan monetary policy makers (mainly the NBM) will have to monitor the market developments very closely in order to avoid material ″derailments″ or macro-economic disequilibria. The Moldovan authorities need to show ″pragmatism″, as IMF recommended in October 2017 for countries implementing programs. Moldova's current good economic potential is there waiting to be harnessed. The country signed a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with the EU in June 2014 (with full effect from 1 July 2016), but, as mentioned, the benefits are still to be fully utilized. In its endeavour, Moldova could be helped by its faithful commercial partners, the EU, IMF, the World Bank and other major international financial institutions.■

Adauga-ţi comentariu