Profit №_12_2023, decembrie 2023

№_12_2023, decembrie 2023

The risks of the external debt

In an article published in April 2023 by the prestigious revue Magazin Istoric*, we have presented Romania’s experience and practices for external borrowings during the last 100 years. At the same time, we have also underlined the risks for a country "living on debt". In the current piece, we would like to make a parallel of Romania’s and the Republic of Moldova’s (Moldova in this article) external borrowing to demonstrate, if needed anymore, that along with the undisputed benefits of foreign borrowing for economic growth and investments, the accumulations of such debts in significant proportions as compared with the economic potential of the respective countries (measured via GDPs) could harm the macroeconomic equilibria and finally the living standards of the future generations.

The issue of public debt, both domestic and foreign, has become during recent years a universal one. The majority of countries (developed, emerging, developing and especially those countries with lower incomes) did finance their budgetary deficits via borrowing from both internal and external capital markets. To put it in simpler words, these countries are (partially) living on debt. Up to 2021, the governmental debt reached the staggering level of $235 trillion (the highest historical level), which is higher by 19% as compared to the level reached before the Covid pandemic started in March 2020. Romania’s external debt evolution during the last century, and more so that from 1989 to date, deserves a detailed analysis due to the major implications this indicator could have on Romanian statehood. It is known that Romania was created in 1918 through the Great Union and defended itself ever since even with a lot of blood and sacrifices. However, losing control of the level of external debt would be an unpardonable and grave mistake of national policy. Moldova’s external debt, which has accumulated during the last three decades since its independence, could be also a reason for concern.

Romania and its foreign debt during the last 100 years

Romania closed one of the most convoluted but glorious pages from its history, the Great Union of 1918, with a relatively modest foreign debt: GBP 33.6 mln, and respectively French Francs 570 mln (whose total equivalent in US Dollars, based on the historical exchange rates, was of 182 mln). However, the financing needs of an economy which had grave wounds from the war and those related to the large process of union of all Romanian provinces in a single state were colossal. Apart from some internal borrowings, the Romanian state contracted on the external markets some stability and development loans. The first one was done in 1929 for $100.7 mln, in four tranches. This was followed by others. The repayment of these loans was very slow and interrupted, some of them being finally liquidated during the socialist years when most external delayed repayments were resolved on a bilateral basis with the creditor states.

A short analysis of exports which followed in the years after the First World War shows that Romania exported large quantities of crude oil, cereals and other unprocessed or incipiently processed products which led to the registration of large trade surpluses during 1922-1924. Crude oil exports, especially to Germany, were the most important and this allowed Germany to attract Romania on its side during the first part of the Second World War. Moreover, as a trend, the exports of 1926 were three billion Lei higher as compared to those of the preceding year. From a large exporter of crude oil during the interwar period and after the Second World War, Romania will become soon an importer of such raw materials, as the internal reserves and production declined dramatically (although new reserves were found on the Black Sea’s plateau). Data published by the former Chrissoveloni Bank during the interwar period shows interesting detailed facts on services as well. During those years, Romania was a net exporter of tourist services, another important advantage which was also lost during the transition to a market economy.

The first monetary measures which had an impact on Romania’s foreign debt during the socialist years must be analysed in the context of the monetary stabilisations of 1947 (at the same time with the nationalisation of the National Bank, foreign currency confiscation, request for gold to be surrender to the central bank, abolishment of the price movements, nationalisation of means of productions and others) and of 1952 (implemented on the Soviet Union’s prescription on monetary reform of March 1950). Romania was the first country member of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) which became a member of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank on 15 December 1972 (after the former SFR Yugoslavia). The accession put its mark on external debt.

One of the main reasons for Romania to become a member of the IMF was the need for foreign currency. Romania asked for such loans from CMEA, but it was declined. As a member of the IMF and the World Bank Group, Romania needed external credits which were used for industry modernisation, improving technologies, financing the irrigation system in the Romanian Plain, development of a transport network and others. Some IMF member countries indeed criticise its programs, but Romania benefited through its promoted financial discipline, especially concerning its foreign debt. As a member of the respective international organisations, Romania had access to the international capital markets as well, which had a positive impact on the economy.

Romania and Moldova: IMF and World Bank membership 1972 and, respectively, 1992

Source: Florea Dumitrescu’s collection for Romania 1972 and Authors’ collection for Moldova 1992

Although external debt, which started to accumulate up to the level of $11 bln, was kept under control, Romania had problems in making all the repayments related to externally contracted loans and it was forced to ask for a rescheduling of its foreign debt in 1982-1983. Rescheduling negotiations took place under the coordination of the Paris Club and London Club for private loans and directly with the IMF and World Bank for loans contracted from these organisations. Then the painful process of forced repayments of the full external debt up to March 1989 started.

Starting in 1973, the Ministry of Finance, which was in charge of the preparation of the Balance of payments up to December 1989, used to send to the IMF a full set of data, including data regarding foreign debt, but the format was a very sketchy one. The control of the external position of Romania was very well fulfilled during the socialist years, taking into account the role the political factor played in the strict control of external debt, especially after Romania had problems with repayments during the early ’80 of the last century (see Magazin Istoric, no. 4/1990). One more note will be worthwhile regarding the collection of the data in those years which was organised via the periodic reports submitted by the commercial banks, the National Bank of the Socialist Republic of Romania and by the economic ministries. It should be noted that the Ministry of Finance did not keep the external accounts of the country.

Currently, Romania has 103,6 tonnes of pure gold, which is deposited in the country and abroad and which based on the international prices as of 31 March 2023 were valued at €6.0 bln. This figure does not include the Treasure from Moscow (91.48 tonnes of pure gold), send for safekeeping in December 1916 together with other gold and silver coins, hard foreign currencies and other national treasures of historical importance and not yet returned.

A major decision regarding Romanian gold was taken during the last years of the communist regime. During 1986-1989, the data regarding the gold reserves held by Romania were not communicated to the IMF anymore and also were not published in the country. One of the reasons for not fulfilling this basic IMF requirement was the fact that in 1986, the country leadership approved the sale of 80 tonnes of gold from the National Bank’s reserve, under the condition that after the full repayment of the foreign debt the gold stock should be replenished. A quantity of 80 tonnes of gold was sold at the best prices in the international markets up to March 1987, by the data published by Governor Florea Dumitrescu (March 1984-March 1989). An amount of $1.040 mln was cashed and this money was used to repay the external debt, together with other amounts obtained from forced exports (especially foods and other basic goods) for which the population needed to make heavy sacrifices. During the second part of 1989, a quantity of 21 tonnes was bought back, but the December 1989 events stopped the process of buying back gold. Up to and including 1992, the gold prices on the international markets were lower than those valid when the gold was sold in 1986-1987, but the new Romanian authorities which led the country after the December 1989 events had other priorities.

After 1990, all data, including the sale and repurchasing of gold, were communicated and appeared as such in the IMF publications. Currently, an important part of the Romanian gold (60%) is kept in London at the Bank of England and is taken into account when Romania borrows from the international markets and when ratings are decided by the international rating agencies, with positive implications on the costs of external debt.

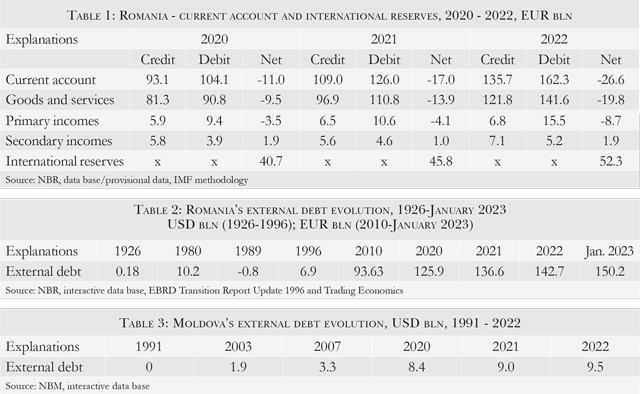

The dramatic events of December 1989 marked the start of the Romanian transition to a market economy. The attributions of the Ministry of Finance related to the control of foreign debt were taken over by the National Bank of Romania (NBR). Currently, NBR publishes monthly the key data on trade and current account deficit. Table 1 shows in a summary format the status of the current account and the international reserves (including gold) over the last three years. NBR also published other provisional data every month. The reporting process was computerised as compared to the socialist period when all was reported on a manual basis.

The preliminary data for 2022 and the first months of 2023 published by the NBR also show large trade and current account deficits. A short analysis of the current account as compared to that registered during 1922-1925 shows major differences in form and substance, if the current situation is compared with that prevailing 100 years ago. The trade deficits of the last two years were in the range of many EUR billions and for the sub-item of tourism services the deficits are also large.

The general impression is now that there is no strict control on what Romania is borrowing, both internally and externally. One of the key instruments used during the last 100 years, namely the Balance of payments, to control the debt has partially lost its monitoring role of the Romanian external position. Moreover, external debt control which used to be exercised through the stand-by programs with the IMF is not exercised anymore as Romania did not conclude any such programs in recent years. The political factors in the country have currently other priorities which are not related to the level of its external debt.

The figures in Table 2 need no further presentation anymore. It is quite clear that the large trade deficits and their parallel current account deficits recorded during the transition period led Romania to a situation in which it lost the net comparative advantage it had as compared to other countries starting the transition in 1990. On one side, the zero external debt reached in March 1989 had internal negative social consequences and created a certain negative perception of external status. On the other side, this situation offered the new Romania a huge chance to focus on the development of a competitive economy, in which the macroeconomic equilibria are observed. Unfortunately, it was not to be.

The accumulation of external debt started during the first years of the transition and has accelerated during the last three years. Indeed, the pandemic which started in March 2020 and continued to date has had significant foreign currency, material and financial costs. This only contributed to more fundamental disequilibria which Romanian registered already during the transition. This is how we reach a situation in which out of total foreign debt, the state has borrowed €57.7 bln as of 31 December 2022.

Romania has currently an economic growth based on consumption, as reflected by the serious trade deficits (imports substantially larger than exports). This is a completely wrong strategy, where consequences were clearly seen during the energy crisis and also during the geo-political crisis in the region (the war in Ukraine started by the Russian Federation). Investments were neglected in all domains of activity (production, infrastructure, agriculture, education, digitalization etc.), but the most concerning trend was the large emigration of the young labour force. Billions of EUR are indeed registered on an annual basis as remittances, but disequilibria are much worse, so the public and private external debt, in the short and long term, has reached around 58% of the country’s 2021 estimated GDP.

Romania, a NATO country since 2004, became a member of the European Union (EU) with full rights on 1 January 2007. These two big achievements were not used properly or efficiently. The utilisation of the EU funds allocated through the National Plan for Recovery and Resilience (NPRR) is more than necessary, but the results in this respect are modest. Large amounts allocated as loans (some of them non-reimbursable) and free technical assistance still wait to be disbursed through the implementation of projects. The case of the €3 bln undisbursed by end-March 2023 because of non-fulfilment of the measures regarding the special pensions is simply alarming!

The whole of Romanian society is concerned with how to stave inflation and avoid the consequences of the energy crisis. There are also concerns about the unclear status of large privatisations, delays in joining the Schengen zone by Romania, its Eastern borders security, special pensions and financing of large deficits of the Pension Institution and others. Many of these are correct, but the reduction of the external debt via reducing budgetary deficits, elimination of trade and current account deficits and incentivising the inflows of capital, is not among the top priorities. Although this became an issue of national interest, the Government, the Ministry of Public Finances (who should control the public external debt), NBR and, more generally, the political parties and the whole society have a permissive attitude on the accumulation of new external debts.

Moldova – over three decades of transition

The case of Moldova shows some similarities, but also a few contrasts, as compared to that of Romania. First of all, in the dissolution and sharing of the assets and liabilities of the former Soviet Union, Moldova opted for "no assets – no liabilities" variant. This means that Moldova, like Romania, started its transition to a market economy with a very important competitive advantage, namely starting this phase without inherited debts. But, like in the case of Romania, this advantage was relatively lost. Data in Table 3 shows a period of fiscal, budgetary and economic prudence which was very important in the first decade of the Moldovan transition, but during the recent times, the evolutions did not have the same trends.

The increase of Moldova's foreign debt during the last three years, which according to the data published by the National Bank of Moldova (NBM) has reached 65.6% of its GDP, requires a closer look. First of all, Moldova, like all other countries has suffered during and in the aftermath of the Covid pandemic, which, it should be noted, has had biblical proportions and corresponding consequences. Moldova, like Romania, was forced to borrow from the internal and external markets to deal with the high costs of the pandemic. Moreover, since February 2022, Moldova, together with Romania, Poland, Baltics and more generally Europe, has had to deal with a human exodus from Ukraine which was unprecedented in the modern era. This was due to the war started by the Russian Federation against a sovereign state, a member with full rights of the United Nations.

During this very difficult period, Moldova managed to get the status of candidate country to accede to the EU, at the same time as Ukraine. The financial and technical assistance that Moldova benefited from the EU must be noted as such, but the costs involved by change of sources to buy energy (oil and derivative products), natural gas and electricity are much higher than the received support. Moreover, like in the case of Romania, Moldova has suffered a massive emigration process of its population, especially of the young generation, which in the short term, but even more so in the medium and longer term, will have negative consequences which are difficulty to quantify. During the recent history of the transition of this country to a market economy, there were periods when the in-flows of remittances from abroad (mainly from EU countries, Great Britain, the Russian Federation, USA and others) have contributed to the GDP formation in large proportions, even up to 20%. This has a very strong positive impact, but losing its young labour force will bring along large economic, financial and budgetary disequilibria. The national fibre of society will be affected if measures are not implemented to, at the minimum, slow down this phenomenon.

External debt – benefits and risks

For both countries, the main slogan is: "For the time being, everything is fine!". This is the opinion of most, even if this is not formally expressed. It is based on the opinion that external borrowing helps with economic growth and stimulates investments if the funds are properly used. This is an over-optimistic attitude!

However, any neglect and/or repetition of the recent delays/mistakes, such as the utilisation of the externally borrowed funds for consumption, can negatively impact the economic equilibria in the long term and could change, as we have mentioned, the social fibre of the nations and societies in both countries. The difficulties of Greece (a member of the EUR zone) to repay its over-sized external debt (accumulated also due to high wages and pensions which were unjustified) should have thought us the relevant lessons. Moreover, the ghost of the former Yugoslavia, a country which was dissolved due to inter-ethnic tensions, but also due to high external debt, is still haunting the Balkans! If the two countries will not control the level of their foreign debts, the international capital markets will do this in both cases at much higher costs, which finally will transform into imported inflation, with serious consequences on the living standards of both populations in the respective countries.■

_________________________________________________________________________________

* The initial article signed by the same authors was published by Magazin Istoric no. 4/April 2023.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Alexandru M. Tanase, PhD, is an Author and Ex. Associate Director, Senior Banker at EBRD London and former IMF Advisor.

Alexandru M. Tanase, PhD, is an Author and Ex. Associate Director, Senior Banker at EBRD London and former IMF Advisor.  Mihai Radoi is a Director of a specialised Investment Fund focused on Eastern Europe and former Executive Director of Anglo-Romanian Bank, London, and previously of the BFR Bank, Paris.

Mihai Radoi is a Director of a specialised Investment Fund focused on Eastern Europe and former Executive Director of Anglo-Romanian Bank, London, and previously of the BFR Bank, Paris.

These represent the author’s personal views. The assessments and views expressed are not those of the EBRD and/or the IMF and/or indeed of any other institutions/sources quoted. The assessment and data are based on information available as of mid-April 2023.

Adauga-ţi comentariu