Profit №_12_2023, decembrie 2023

№_12_2023, decembrie 2023

Romania and Moldova - parallel destinies in banking transition

The banking sectors of the two countries have been fields in which the transition to a market economy that started some three decades ago has brought the most profound transformations. In fact, the current banking systems are almost unrecognisable if compared with those existing by the end of 1989/1991. The most powerful argument is, for instance, the share of the private sector in the Romanian banking sector which at the time was 0% and which three decades later reached 91.9%. The situation is similar in the Republic of Moldova. However, meanwhile many major events have taken place during this period of time. A short presentation of these different banking destinies is worthwhile to be made.

Romania - The end of socialist banking sector

The December 1989 events found the Romanian banking system in a super-centralised shape, with a central bank established long ago in 1880 (National Bank of the Socialist Republic of Romania) and 4 specialised banks (Investments Bank (IB), the Romanian Bank for Foreign Trade (RBFT), Agricultural Bank (AB) and the Savings and Consignments House (CEC). This was radically transformed in September 1991. In accordance with the normal practice, the functions of the former National Bank of the Socialist Republic of Romania (NBSRR) were divided into commercial ones and central bank functions. The National Bank of Romania (NBR) was established as the central bank, while the Romanian Commercial Bank (RCB) took over the previous functions from the former NBSRR which were specific for a commercial bank, being empowered to handle with priority the industrial sector and transport and commerce. At the same time, other commercial banks were established/re-organised as universal ones. The banks’ universalisation, both with regards to the handled sectors and regarding the range of services and transactions implemented, was one of the key objectives of the monetary policy soon after 1989. The development of the private sector within the banking system was the second such major objective. (Fig. 1).

The beginnings of the banking transition

In the early days of Romania’s transition to a market economy, for a period of time, the banking system was formed of the 4 large commercial banks (Romanian Commercial Bank, Bancorex (the former Romanian Bank for Foreign Trade), Agricultural Bank and the Romanian Development Bank (RDB, former Investments Bank)) inherited from the socialism and a large number of private banks, including 9 branches of foreign banks such as: Chase Manhattan Bank, ING Bank, Banca Anglo-Romana, Société Générale, etc. In addition, in July 1996, the Romanian Parliament approved the re-organisation of the Savings and Consignments House (CEC, currently CEC Bank) as a banking entity with the state as single shareholder.

In a very detailed analysis of the actual situation during those starting years, it is easy to observe that the Romanian banking sector was comprised from a multi-type banking societies whose capital had very diverse sources. A wide rage of commercial banks were re-organised, established or expanded in a relatively short period of a few years only. The foreign capital started to become more and more present in the Romanian banking sector (by end-2018, it reached 75%). At the very start of transition, the commercial banks had a net creditor position in their relationship with the foreign entities. For instance, as of 31 December 1996, total net creditor was of some USD 386 mln at the historical exchange rate. Currently, the 34 commercial banks authorised by the NBR have total net assets of Lei 451.1 bln (EUR 96.7 bln as of end-2018).

Apart from a nominal growth which could be labelled as substantial at the start of transition (mainly explained due to the depreciation of the Leu exchange rate), one can also observe that the net creditor position signalled the existence of international reserves held by the commercial banks in those years, which in turn was the result of an attitude which was constantly present within the Romanian banking system to accumulate the foreign currency. On the other side, in accordance with the data published by the NBR for end-1996, one can see that this was in a net debtor position of Lei 2155.7 bln or some USD 534 mln (much larger than in the previous years). This signalled the start of a tendency which had become more and more worrisome, namely the start of the accumulation of a substantial foreign debt (managed by NBR), which by the end of March 2019 reached at EUR 99.8 bln (some 50% of GDP).

The Romanian monetary policy was prepared and implemented by the NBR, an institution empowered to conduct an independent monetary policy for which it has been and still is held responsible by the Parliament. A distinct law was issues for the commercial banks activities in 1991. Despite all these, the monetary policy at the beginning of transition was very convoluted and issued in inflationary or hyper-inflationary conditions and many times under immense political pressure which had nothing to do with the market economy.

The December 1989 events found the Romanian banking system in a super-centralised shape, with a central bank established long ago in 1880 (National Bank of the Socialist Republic of Romania) and 4 specialised banks (Investments Bank (IB), the Romanian Bank for Foreign Trade (RBFT), Agricultural Bank (AB) and the Savings and Consignments House (CEC). This was radically transformed in September 1991. In accordance with the normal practice, the functions of the former National Bank of the Socialist Republic of Romania (NBSRR) were divided into commercial ones and central bank functions. The National Bank of Romania (NBR) was established as the central bank, while the Romanian Commercial Bank (RCB) took over the previous functions from the former NBSRR which were specific for a commercial bank, being empowered to handle with priority the industrial sector and transport and commerce. At the same time, other commercial banks were established/re-organised as universal ones. The banks’ universalisation, both with regards to the handled sectors and regarding the range of services and transactions implemented, was one of the key objectives of the monetary policy soon after 1989. The development of the private sector within the banking system was the second such major objective. (Fig. 1).

The beginnings of the banking transition

In the early days of Romania’s transition to a market economy, for a period of time, the banking system was formed of the 4 large commercial banks (Romanian Commercial Bank, Bancorex (the former Romanian Bank for Foreign Trade), Agricultural Bank and the Romanian Development Bank (RDB, former Investments Bank)) inherited from the socialism and a large number of private banks, including 9 branches of foreign banks such as: Chase Manhattan Bank, ING Bank, Banca Anglo-Romana, Société Générale, etc. In addition, in July 1996, the Romanian Parliament approved the re-organisation of the Savings and Consignments House (CEC, currently CEC Bank) as a banking entity with the state as single shareholder.

In a very detailed analysis of the actual situation during those starting years, it is easy to observe that the Romanian banking sector was comprised from a multi-type banking societies whose capital had very diverse sources. A wide rage of commercial banks were re-organised, established or expanded in a relatively short period of a few years only. The foreign capital started to become more and more present in the Romanian banking sector (by end-2018, it reached 75%). At the very start of transition, the commercial banks had a net creditor position in their relationship with the foreign entities. For instance, as of 31 December 1996, total net creditor was of some USD 386 mln at the historical exchange rate. Currently, the 34 commercial banks authorised by the NBR have total net assets of Lei 451.1 bln (EUR 96.7 bln as of end-2018).

Apart from a nominal growth which could be labelled as substantial at the start of transition (mainly explained due to the depreciation of the Leu exchange rate), one can also observe that the net creditor position signalled the existence of international reserves held by the commercial banks in those years, which in turn was the result of an attitude which was constantly present within the Romanian banking system to accumulate the foreign currency. On the other side, in accordance with the data published by the NBR for end-1996, one can see that this was in a net debtor position of Lei 2155.7 bln or some USD 534 mln (much larger than in the previous years). This signalled the start of a tendency which had become more and more worrisome, namely the start of the accumulation of a substantial foreign debt (managed by NBR), which by the end of March 2019 reached at EUR 99.8 bln (some 50% of GDP).

The Romanian monetary policy was prepared and implemented by the NBR, an institution empowered to conduct an independent monetary policy for which it has been and still is held responsible by the Parliament. A distinct law was issues for the commercial banks activities in 1991. Despite all these, the monetary policy at the beginning of transition was very convoluted and issued in inflationary or hyper-inflationary conditions and many times under immense political pressure which had nothing to do with the market economy.

The lack of monetary and financial discipline from the part of the economic agents and the very low trust of the population in the national currency (especially during 1990-1992) had a strong negative impact on the monetary policy. Many times, the Romanian monetary policy was “indulgent”, a fact which contributed significantly to the start of the inter-enterprise financial arrears (17% of GDP in 1996). Also, there were years when the monetary base was expanded much faster than the GDP increase, which exacerbated even more the inflation.

The exchange rate policy issues were at the centre of debates with the IMF’s representatives (Romania is a member of the IMF and the World Bank since 1972) and those of other international financial organisations. During the first part of 1996, NBR had interfered with the foreign currency market and took restrictive measures regarding the right to quote the Leu. These actions led to the suspension of the disbursements from the IMF within the December 1995 arrangements with this institution. At the same time, requirements on the capital adequacy ratio (minimum 8%) of the banks and on the open foreign currency position (maximum 10% of banks’ capital) were introduced. However, some prudential banking requirements were pure and simple ignored up to the big scandals in the banking sector such as Dacia Felix, Credit Bank, SAFI, FNI, etc. Within this restrictive monetary policy during 1996, the NBR withdrew, for the first time during transition process, the banking licence of one bank as was the case of Fortuna Bank. At the same time, in the case of other banks such as Dacia Felix and Credit Bank, the NBR stopped its financial support on 16 July 1996 after overdraft credits of Lei 1,700 bln were already extended to the two banks. Under such circumstances, the analysts dealing with the Romanian monetary policy, rightly remarked that what was done was, “too little and too late”. Within the context of the challenges which were faced by the Romanian banking system, it will be fair to mention that the NBR revised in July 1996 its norms regarding the minimum reserves requirements and that the banks’ foreign currency exposure was constantly controlled by the monetary authority.

Following the financial problems related to the investment funds SAFI and Credit Fund, the NBR and the Ministry of Finance issued in May 1996 only new rules regarding the correct management by these funds of the amount of money invested by companies or population. Like in many other cases, these regulations were issued only after serious scandals erupted. The small investors practically saw their savings drastically reduced, if not even lost in full. The regulations introduced on the guarantee of deposits made by the individuals with the Romanian banks of up to Lei 10 mln/customer (the Deposits Guarantee Fund in the baking system was established in 1996), had once again confirmed that the authorities, including NBR, acted only after major events took place on the capital market. Such cases drastically diminished the trust of the population in the Romanian leu and in its banking and financial system. Currently, the limit for guarantees by the Deposits Guarantee Fund is of EUR 100,000/customer/bank, in accordance with the EU’s requirements and practice, as Romania is an EU member since 1 January 2007 as well.

Like in the case of many other countries in transition, the interest rate in Romania has been under the remit of the NBR. The central bank has been constantly under a strong pressure from the political factor to reduce the level of interest rates in order to support the economic recovery of many productive or commercial companies. The Romanian monetary authorities were blamed that they had manipulated the level of interest rates in accordance with the short terms needs of the Leu’s exchange rate. The ROBOR scandal in 2019, with very clear political connotations, is just one example. On 15 May 2019, the level of the monetary policy interest rate was maintained at 2.50% per year.

Moldova - Modest beginnings and complex evolutions

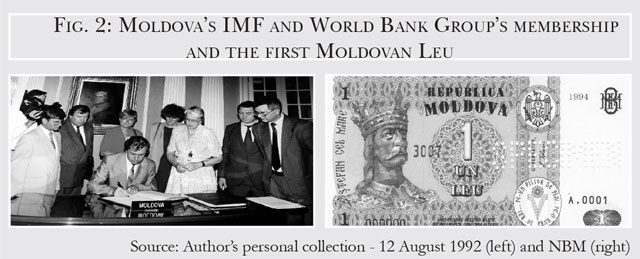

Moldova started its transition from an altogether completely different positon. The country declared its independence on 27 August 1991, but there was no banking basic infrastructure. First of all, Moldova was not a member of the IMF and the World Bank Group. This was the country’s first priority and the membership was achieved on 12 August 1992. Then the country had a very young central bank, but it had not its own currency. The National Bank of Moldova (NBM) was established on 4 June 1991, but the country had continued to use the rouble (the Soviet/Russian ones) and coupons for a good period of time. The Moldovan Leu was introduced only on 29 November 1993. (Fig. 2).

There were no moderns working norms for the banks, their balance sheets were still denominated in roubles and the first international audits were undertaken only in 1995 upon the EBRD’s requests. Victoria Bank and Moldova-Agroindbank were the first banks internationally audited. These were followed by many good years of excellent cooperation with the international financial organisations which granted credit lines and/or technical assistance to the commercial banks and the NBM, as the case may be. Meanwhile, the first issues of the banking sector transition started to emerge.

Moldova’s foreign debt started to accumulate at a very fast pace up to the level of USD 7.3 bln as of end-2018 (in accordance with the NBM’s data), which represents 62.1% to its revised GDP, according to the World Bank estimations. (https://tinyurl.com/yyg6pgzn)

One other example was the change of NBM’s management in 2009, after which the monetary supervision had deteriorated. Then the Russian banks used the Moldovan banks to launder immense amount of money (some USD 20-22 bln) up to May 2014 and the non-performing loans started to increase up to non-sustainable levels. All of these were followed by the large fraud in the banking sector of USD 1 bln which let to the crash of 3 major commercial banks of Moldova in 2015 and subsequently to the cover of the loss by the state budget. All these negative evolutions have led to the interruption of the country’s external financing during recent periods. During the almost 3 decades of Moldovan banking transition there were, of course, many good achievements as well (the organic growth of the commercial banks, international credit lines for SME financing, increasing transparency of the shareholders of the key banks during 2018-2019, foreign direct investment in banks, etc.), but all of these were unfortunately shadowed by the resounding scandals. It is quite clear that the transition process was not successfully concluded, even if after April 2016 a new management was approved for the NBM.

Privatisation of some commercial banks in the two countries

In Romania’s case, this was a field in which the hesitation and inconsequence of the authorities had negative effects on the Leu’s stability and had determined the attitude of “let us wait and see what happens” from the investors’ side. For instance, the law approved by the Parliament for the approval of the Mass Privatisation Program in 1995 stipulated that a special draft law will be submitted to the Parliament by the Government related to the banks’ privatisation. Many versions were debated and rejected or delayed. The former State Property Fund (FPS) and the former 5 Private Property Funds (FPPs, currently Financial Investment Societies (SIFs)) were on divergent positions regarding the banks transfer of property.

In December 1996, the Program of Main Macro-Stabilisation and Development of Romania up to 2000 was prepared and published by the Government of Romania and which had as a strategic objective ″privatisation of state-owned commercial banks″. After the approval of an adequate legislative framework, organisational measures were required in order to start the actual privatisation of some of the large commercial banks.

One of the issues with which the Romanian authorities had to handle in those days was that of a clear option regarding the banks which were supposed to be privatised. The Government in office up to December 1996 had launched a few potential privatisations in which were included in a successive order RDB, Bancpost and finally even Banca Agricola. BCR was taken over by the Austrian Erste Group in 2006 well after it had “acquired” BRCE (in reality BRCE, subsequently renamed Bancorex, was liquidated in 1999 in the aftermath of grave mistakes concerning prudential regulation), Banca Agricolă was bought by Raiffeisen Group (RZB), Austria during 1999 - 2001 at a very modest price of some USD 60 mln and BRD also bought by the French group Société Générale in a few successive phases during 1998 - 2004. (Fig. 3).

The hesitation of the Romanian authorities (both of the Government and the Parliament) was also determined by a range of complex technical issues which needed to be resolved when the question of the privatisation of a large state-owned commercial banks was raised. One of these issue was related to the selling price for the shares to be sold. As an example, this raised serious technical and practical difficulties in determining the market price of RCB. The privatisation of this bank failed/was delayed quite a few times until the state finally sold its shares to Erste Group in 2006. One other basic requirement was the availability of annual reports issued by international auditing firms.

The story of privatisations of banks in Moldova is quite different. The dissolution of the former Soviet Union and the declaration of independence by the Republic of Moldova on 27 August 1991 generated confusion in the banking sector but, at the same time, created also real opportunities. The former branches of the Soviet banks declared in a short period the break-up of the relations with the Soviet “mother” banks and distributed their share capitals to some shareholders which were in fact their former clients. This was the reason of very large number of shareholders in the case of the key banks in Moldova, an issue which had persisted until a few years ago when the large commercial banks (Moldova-Agroindbank, Moldindconbank, Mobias Banca and Eximbank) were taken over by transparent shareholders or had their banking licences withdrawn as was the case of Banca Sociala, Banca de Economii and Unibank. The story of the establishment of the first private commercial bank C.B. Victoria Bank in 1989 and its destiny is fascinating and would deserve a special presentation. In this respect, a detailed presentation of its destiny will require many volumes. The photos in Fig. 4 below present the start and the present of this bank as they were shown by the Founding President of this banking experiment which finally, after many challenges, succeeded with the EBRD and other international financial institutions’ support. Currently Moldova has only 11 commercial banks with full banking licence.

Romania and Moldova - Banks bankrupted, taken over or dissolved during transition

Concerning Romania, at a first sight, in the banking sector there were at least 20 banks which were established and then disappeared during the transition period, of which 10 banks were bankrupted, dissolved or taken over under emergency circumstances. The most famous case was that of Bancorex, (former BRCE, taken over by BCR on 30 July 1999), but also those of Volksbank (taken over by Banca Transilvania (BT) on 31 December 2015) and of Banca Turco-Romana (bankrupted on 3 July 2002) all of which had grave image impact on the banking sector in which the trust is the most precious asset.

Similarly, during the same period, large banks were taken over due to the difficult situation of the shareholders (Bancpost, initially privatised with GE Capital and finally held by EFG Bank, Greece and taken over by BT in 2018 due to a difficult situation of the ″mother″ bank and more generally due to the economic situation of Greece), while Banca Carpatica was taken over by Patria Bank due to integrity issues related to some of its key shareholders. Other banks (Columna Bank, Bankcoop, Dacia Felix, Demir Bank, Nova Bank, etc.) bankrupted pure and simple after 2000 or were taken over due to non-efficient and/or corrupt managements.

Moldova has also many commercial banks which were bankrupted or had their banking licences withdrawn. Bancosind, Investprivatbank, Banca Guinea, Banca Turco-Romana, Banca Basarabia, Universalbank and others failed following managerial mistakes made by the managers of those banks and, respectively, by the key shareholders, but the most resounding case was that of Banca de Economii, Banca Sociala and Unibank in 2015 which lost their licences in the aftermath of a large fraud which was without precedent in the banking transition history in this country and in the region of USD 1 bln (see Kroll I Report). The loss of MD Lei 14 bln (at the historical exchange rate) was transferred to the state budget and its recovery is slow and almost at the beginning after so many years. Currently, there are 7 commercial banks that have liquidators appointed by the NBM.

The lessons learned from all these cases must be analysed throughoutly by the commercial banks and first of all by NBR and NBM which have, by law, licencing and supervision attributions. In this respect, we consider that the banking transition was not concluded, irrespective of the fact that Romania has been an EU member for more than a decade and Moldova has a Deep and Comprehensive Agreement with the EU since June 2014.

During the certain years at the beginning and up the these days, politicians of vary orientations from both countries have tried to resolve/improve these problems via issuing ordinances/Government decisions which stipulated more for administrative measures meant to resolve economic basic issues. In a market economy, however, the key economic and banking issues are not supposed to be resolved via administrative orders.

The economic laws of the market economy should prevail. The future economic analysis will need to articulate very well this fundamental aspect. And not only this. The time of clearly establishing responsibilities for the grave mistakes made and/or for proven corruption acts is already overdue.■

____________________________________________________________________________________

Alexandru M. Tanase is an Independent Consultant and Former Associate Director, Senior Banker at EBRD and former IMF Advisor. These represent the author’s personal views. The assessments and views expressed are not those of the EBRD and/or the IMF and/or indeed of any other institutions quoted. The assessment and data are based on information as of end-May 2019.

Alexandru M. Tanase is an Independent Consultant and Former Associate Director, Senior Banker at EBRD and former IMF Advisor. These represent the author’s personal views. The assessments and views expressed are not those of the EBRD and/or the IMF and/or indeed of any other institutions quoted. The assessment and data are based on information as of end-May 2019.

Adauga-ţi comentariu